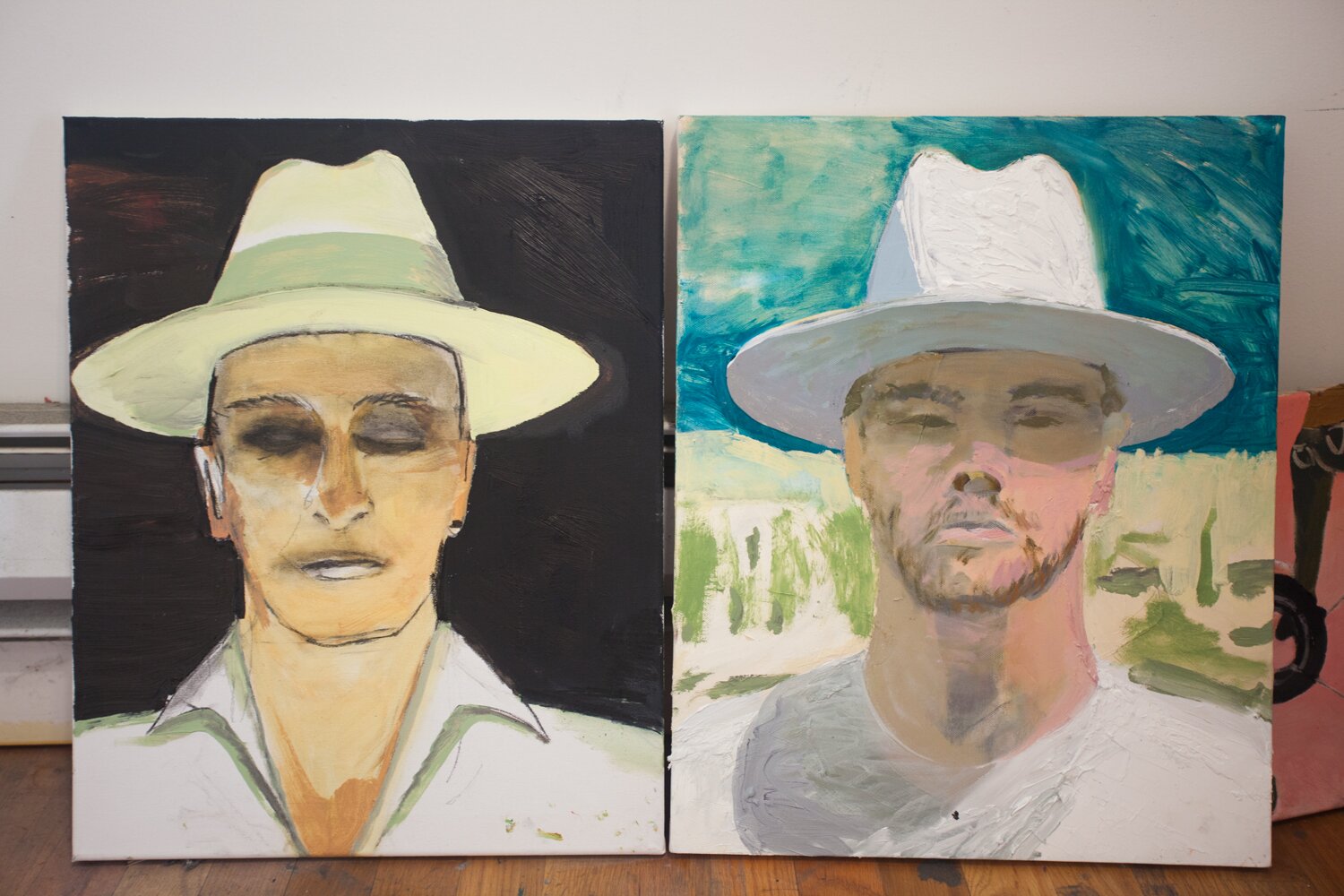

Jason Mones’ paintings are done in a humorous self-deprecating manner with masculine imagery like shields, beer, and meat as well as castration. His current body of work reflects on the current political landscape in the United States conveyed through loose narratives with thick layers of paint. We were able to visit Jason Mones just as he was gearing up for his recent show, ‘Force and Fumble’ at Tiger Strikes Asteroid in LA.

F: Can you start with describing your process? How do you start your paintings? It feels like you are not painting from observation. Do they start with sketches and sources or more from memory?

J: My process usually begins by reflecting upon recent paintings made within the last year and looking at what the larger narrative might be. I usually start by drawing directly on the canvas working from my imagination. Nothing is precious in the studio, and I allow myself to build and destroy anything that doesn’t feel right. This most recent body of work started by feeling compelled to discuss the current political atmosphere and its relationship to certain tropes of heteronormative masculinity. It’s a strange time in our human history and it frightens me. Most of the paintings evolve through the process of discovery and when all the figures and scenes feel right, then I begin working in details from some pictures or preparatory sketches, but mostly it’s out of my own head.

F: Your work explicitly confronts a male point of view. There’s a conflict between excessive masculinity and also a (non-literal) castration of the figures. Can you talk a bit about this and where you see your paintings going from here?

J:For many reasons, the male point of view is a wellspring of creativity for me. There’s a mythology wrapped up within a gaze that is forever fascinating. I began making these portraits because I wanted the audience to come face to face with the angry male populism that is pervading our cultural and political environment. I believe it is a larger influence than what most of us want to imagine.

You’re right to pick up on a non-literal castration. I keep thinking of what Nicole Eisenman said about gender (She’s one of my favorite painters), how she wishes gender would just go away, and I agree basically. However, gender has shaped so much of our history, and it still pervades in so many ways that I feel compelled to paint its flaws. The castration of the figures is a wishful nod to the obsolescence of male superiority. And this at times has taken on an implosive, or self destructive quality to the figures. However, with the recent larger paintings, I felt the need to illuminate the outward destructive forces as well. It’s 2016 but in many ways our systems are medieval.

Where will I will go from here? After a body of work has been completed, I always want to completely change my direction and paint something else, or make sculpture. But so far, I always come back to the body in painting. I ruminate constantly on how many people there are in the world and what impact were having upon it, and I have a compulsion to discuss our modern conflicts. There was an article written a year or so ago that spoke of the body as a failure in art and the wonderful things that come along with those “failures”, and that imperfect challenge always engages my creative mind.

F: There’s a non specificity in the places and subject – the figures climbing over a fence could be an airport or a shopping mall. The group of male portraits could be off duty police officers or southern farmers. Do you feel that by paring down the specifics you can get closer to describing the characters and places?

J: I find that a bit of non specificity can be used to engage the imagination of a viewer. Each person brings their trunk of experience when analyzing an image, and this subjectivity helps feed the core of our continual interest in a work of art. Most places I’ve seen in the world have the similar, human-made landscapes-all from the 20th century. Parking lot buildings, old factories and airports all have that same utilitarian look. We are all familiar with these places. Portraits, too, have this ability to make us try and identify the individual, either from memory or picking up on visual cues to familiarize ourselves with that “type” of person.

F: You create characters placing them in certain scenarios or loose narratives that sometimes border on magic realism. Where do these narratives come about? Are they based on news stories? They seem very American like from American folktales.

J: The narratives usually begin to formulate from outside events, both fictional and real. If I’m reading the newspaper or a book and there is a moment that strikes my imagination then I’ll use that as an entry point to begin a painting, but I don’t fixate upon it. I let it unfold and evolve over time. Some of the recent work plays with themes of American folklore and our fascination with shows like Duck Dynasty. This myth of manifest destiny that has pervaded as a dominant narrative in our country is terrifying how it keeps moving through time as an influence, like some ghost we can’t get rid of.

F: What is a typical studio day like?

J: Once I’m in my studio, I try to unplug from the world to keep the wheels spinning. I’ll get some music playing or a podcast going and suit up with gloves and my apron. I have to trick myself into picking up the paintbrush, so I’ll start by looking at what needs work, adjustment, change of color. I’ll fix a small thing, and once I’m painting, its leads to an escalation of engagement with the material. There are frustrations abound, but leaps of enjoyment speckled here and there.

F: How long does it take to produce a painting?

J: I think every painter wrestles with this question and I don’t think there is a given answer. Some paintings can happen quick and fresh. But it can be suspect. You work on something and it looks great….too great, and you have to come to terms with its existence. Then there’s this point where you have to bust it up, and at that moment, you reach a place within a painting where there’s something deeper that comes to fruition. For me, a challenge of building the unknown and bring it into the world is more important than obsessing over its aesthetic. Some paintings take years, while others are made in a few weeks.