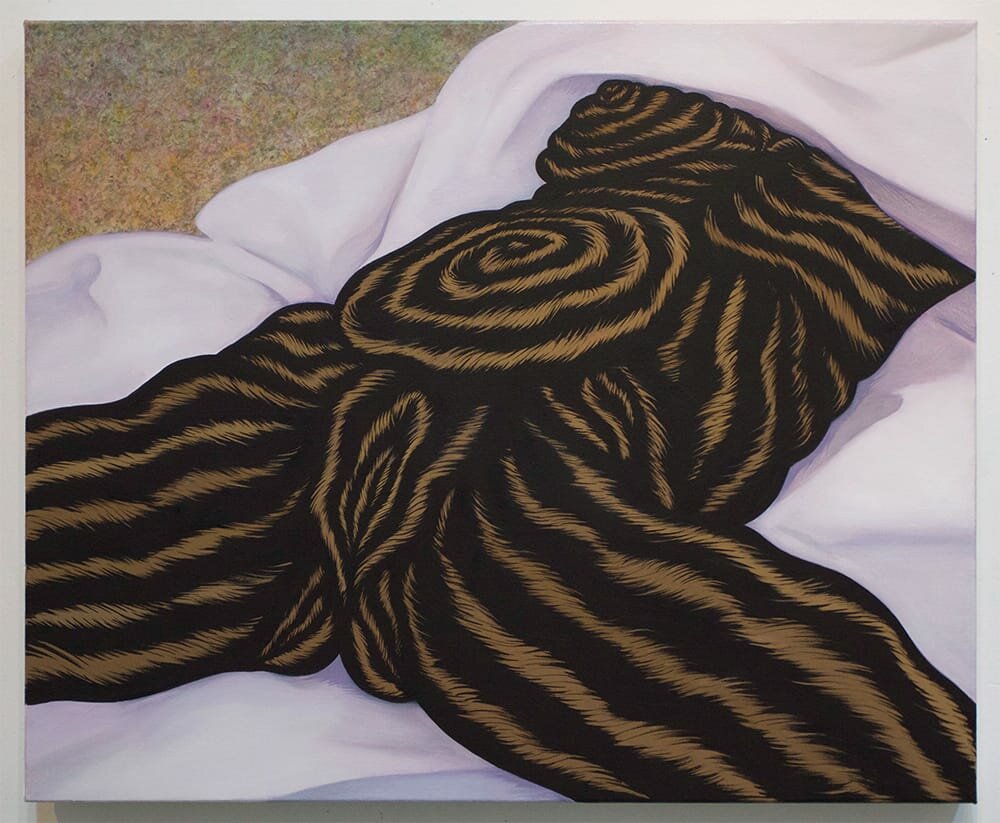

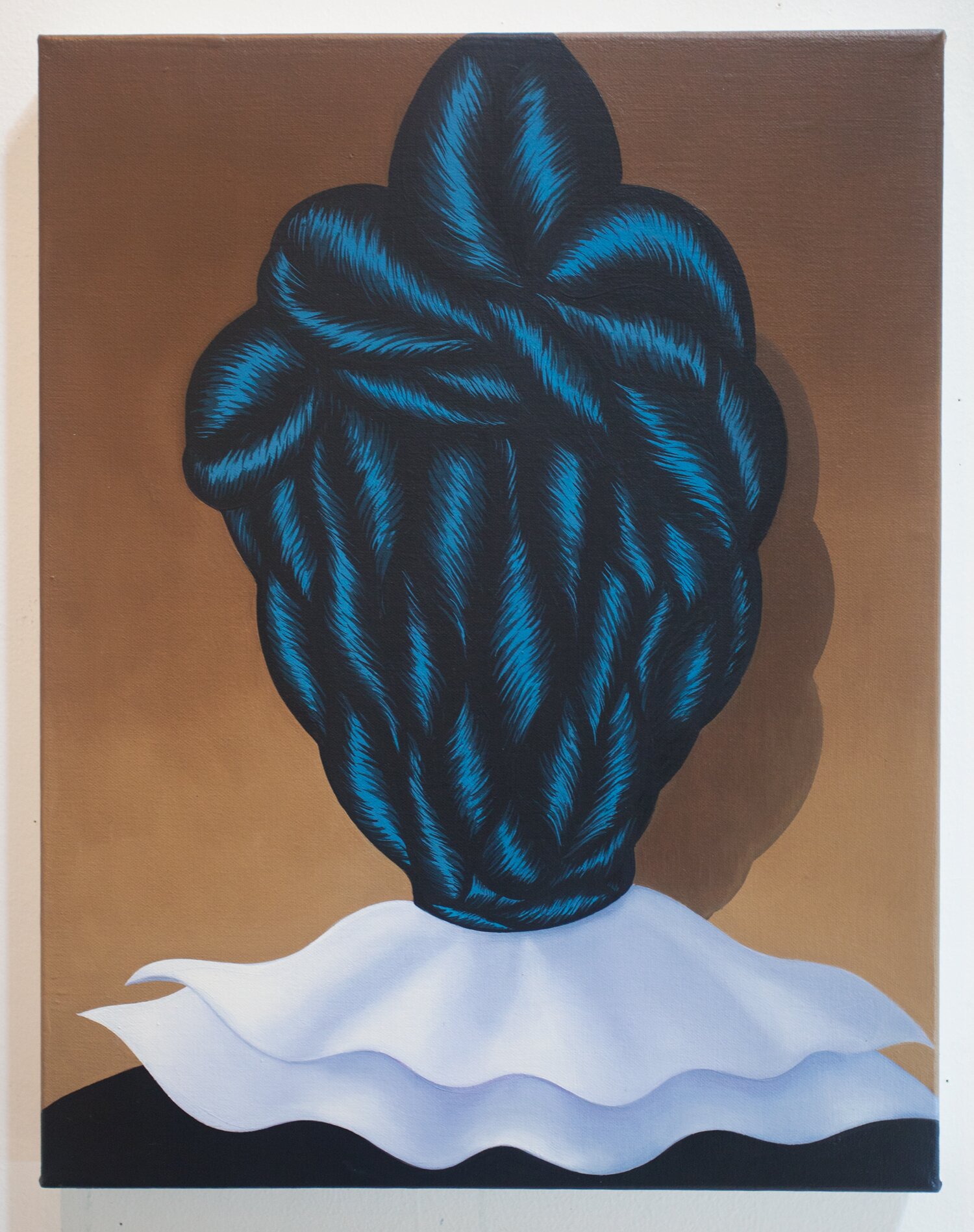

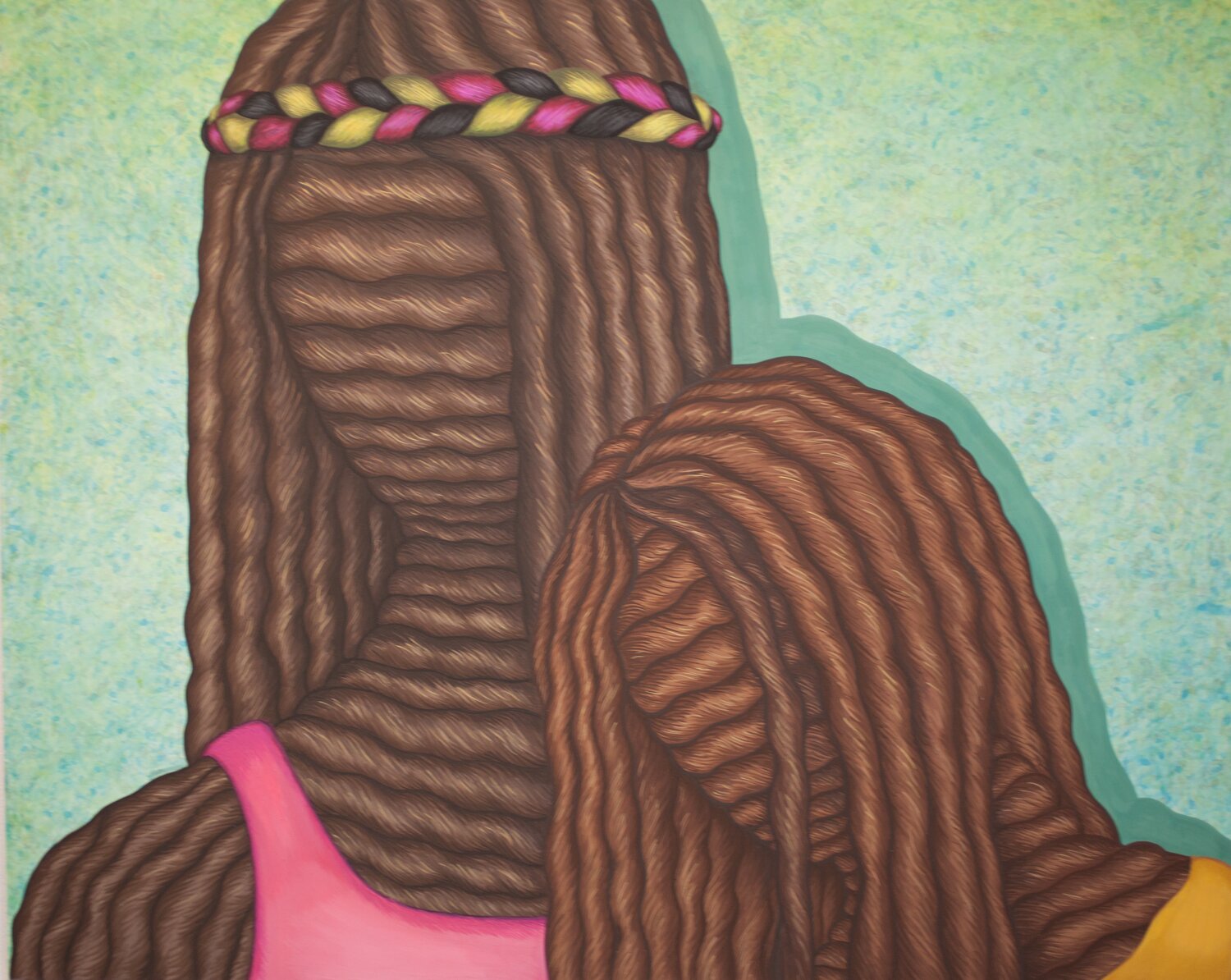

Evoking references to 19th and 20th century European portraiture, the female figure in all its glory is proudly on display in Julie T. Curtiss’s paintings but unlike traditional portraiture, their faces are intentionally obscured. Instead of voluptuous breasts, delicate gestures and a demure gaze, the female figures feature sharp pointy breasts, gnarled fingers, and bodies composed of a mesmerizing pattern of hair. At once intriguing and grotesque, the surreal paintings invite the viewers to consider these female figures as more than a one-dimensional archetype.

During our studio visit, Curtiss walked us through her process, her infatuation with hair and her strong kinship with Chicago imagists.

Julie T. Curtiss is an artist living and working in East Williamsburg/Bushwick. Her work will be in the group show, Post Analog Painting II opening April 7th through May 14th at . She is currently working on her solo show at opening this upcoming October 2017.

F: Can you talk about your process?

J: There are several ways for me to start a new painting. Often an idea will spark out of the narrative I have constructed over the years. Or I will think of my visual vocabulary and pull out elements, try to assemble them until they form a composition and a story. More rarely, I will start from an existing painting I have seen or the still from a movie… Once I found an idea, I will capture the image on paper; sometimes I will work several sketches of the same idea, simplifying the forms and the lines, until the composition satisfies me. These sketches can be extremely crude. If the sketch doesn’t work, I have to put the idea on hold.

F: Where are you finding your references from?

J: I think I find a lot of my inspiration in French and European painters from the 19th and 20th century… because a lot of these artworks are very popular, I enjoy how they worked their way into people’s mind subconsciously. They became iconic and I love using that cultural/collective added material, in subliminal or explicit ways. It can be just hint, a fragment or by re-using the whole composition, in a pastiche like way… I have some very early memories of visiting the Orsay museum as a child with my parents. I was awestruck with the artworks, the sensuality to the sculpture gallery, the feel of the old train station. I believe my images are connected to this first intimate contact with art.

As for my approach, I feel a strong kinship with the Chicago imagist. I studied a semester at the art institute of Chicago about ten years ago, however I was only vaguely aware of them at the time… I don’t think I understood what they were about. Now, I relate to the pop and graphic aspect of their vibe, but also to the humor, the low key. I discovered Christina Ramberg and Ray Yoshida about 4 years ago. I feel the closest to them. I love Roger Brown too.

F: Can you talk about your studio space?

J: I feel so lucky I found an affordable studio space located only two blocks from where I live -East Williamsburg/Bushwick. I am on the floor of a large complex of old factories, converted into art studios. I like my landlords, they are high quality framers and they are very respectful of artists. My only regret is its convenient location next to a gas station, which means easy access to Dunkin doughnut and all kind of tempting junk food!

F: There is a sense of narrative that seems non-explicit, at times it seems

as though you are dealing with universal myths and other times, they seem like created specific narratives.

J: Yes, I am glad you picked up on that. I would use the word archetypes instead of universal myths though, just because in the myth there is the notion of hero and journey but the archetype is more focused on the recurring themes and motifs at the heart of the myths. I am fascinated with Carl Gustav Jung theories about archetypes particularly the shadow and the anima. I am interested in the shadow archetype because I like to bring forth what’s culturally repressed and kept in the dark in my images. And the Anima, which represents the feminine inside male identity, captivates me because of its projections are at the center of artistic imagination historically: the Virgin Mary or Eve for example.

But to come back to the seeming contradiction between general and specific narratives, I could almost say I would like to capture the language of dreams. Dreams can be extremely precise and general at once. Sometimes, details seem so charged with meaning; it leaves an impression on you even after you wake up, and more than often the explanation still eludes you. Ideally, I would love to achieve this feeling when I work. I’d like to draw viewers in, with familiar ideas or imagery, and half way into it, I kind of highjack the story with my own idiosyncrasies.

F: Can you talk about the sexual nature of the work exploring on gender roles. In particular, the braids elude to a notion of youth as well as a certain censoring of the female body literally binding the figure in braids.

J: Yes! For some reason, hair showed up very early in my practice.

Just formally, painting intricate braids is a way for me to space out and get into a repetitive action, a bit like knitting. Also, it’s a very malleable element to paint composition wise. Actually, from 2010 to 2012, I made a whole body of works depicting imaginary landscape, just by using a bush stroke, similar to black hair or wisps. The result was very organic and intuitive. Now I use the same kind of effect but more sparingly: with hair and bodies/objects made of hair. I enjoy the effect it has on the eye; it’s hypnotic and satisfying to look at.

As for the sexual or gender aspect of it, when I come to think of it, hair is a natural asset women use to seduce. Sometimes, assets can define you. Women can get trapped, or trap themselves in representations. Beautification can become constraints, in other words bindings. Women’s bodies are objectified/commoditized by men and women themselves, by cultures…etc. The tension between nature and culture is important in my work and I find the negative aspects of it just as interesting as the positives. There is something to the mane/the wild, as opposed to the braid/the domesticated, that captivates me.

F: It seems that you work naturally rather small and intricately with gouache and acrylic on paper, but you have been moving to larger scaled oil and acrylic paintings. How has this changed the work and image? Do you find that you are making different decisions?

J: I have been making works for sixteen years now and I have always alternated between small works and larger scaled works. I started the body of work you now know with a small series of gouaches on paper in 2015. It allowed me to work through ideas very fast. It was very fun and stress free, just sitting at my little table and painting my images. But at some point I felt I would have to challenge myself a bit.

I am not sure I am trying to achieve the same things on paper and on canvas but for one thing, the standing position forced me to be more physical and involved in the painting process. Also I find it hard to paint as detailed when standing up. So maybe there is a little less comfort and noodling around in my works on canvas. I also feel that some works don’t translate well on a large scale and that when things are blown up, composition problems are less forgiving. Transitioning to larger work was difficult, especially because I started to use oil as well. My art tended to be very graphic on paper and the addition of oil to my practice brings a softening touch, which balances with my hard edge, flat esthetic, and sets my practice more in the tradition of painting.

You can check out more of Julie T. Curtiss’s work at her website .

Coming up shows:

Post Analog Painting 2, The Hole Gallery, New York (NY) du April 6th to May 14th 2017

Duo exhibition with Mathew F Fisher, Monya Rowe Gallery, Saint Augustine (FLorida) May 13th to June 25th 2017

Solo Show, 106 Green Gallery, Brooklyn (NY), October 2017

“I discovered Christina Ramberg and Ray Yoshida about 4 years ago.” Replace “discovered” with “ripped off”.