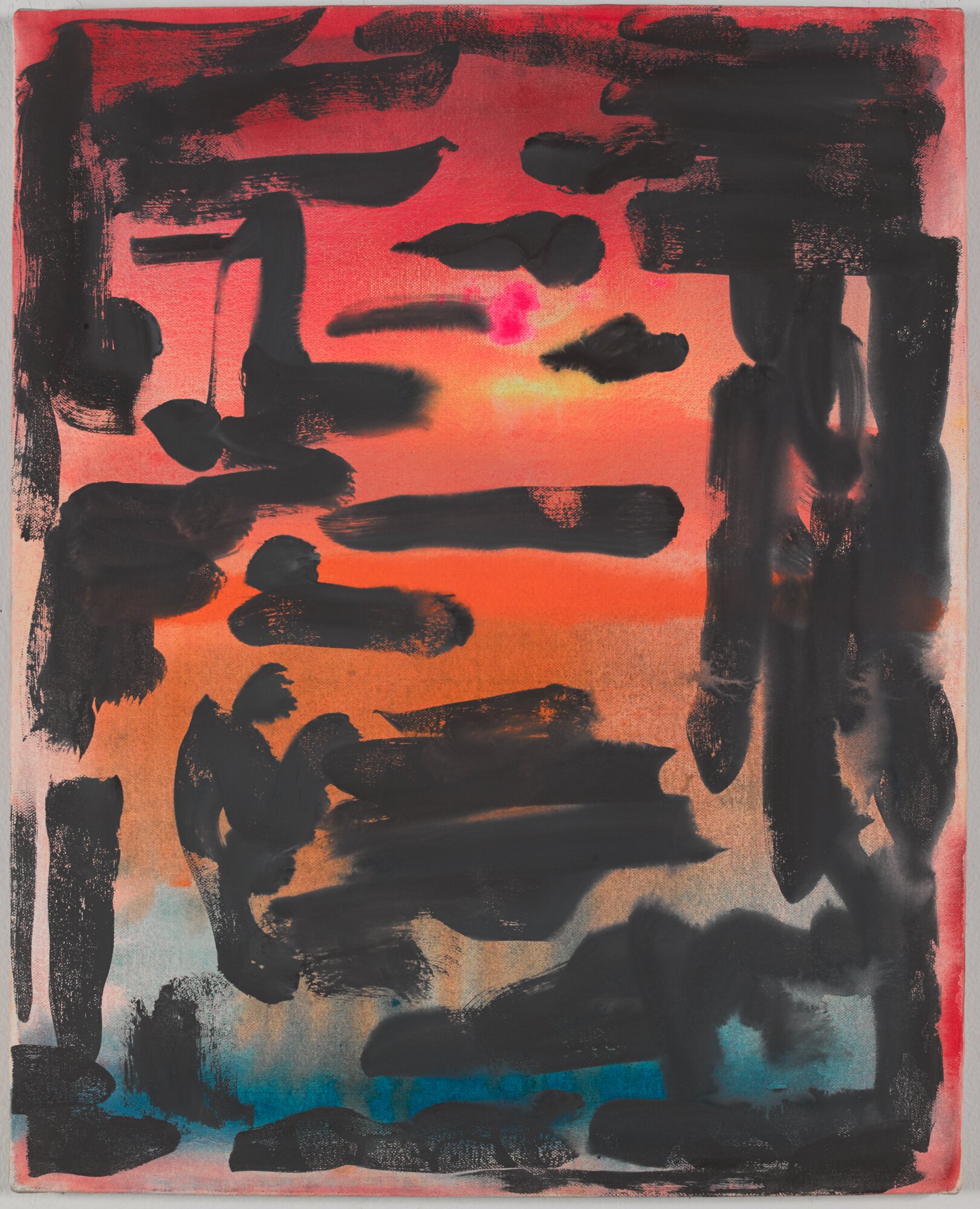

invited us into his expansive shared studio space where we got the opportunity to get a better understanding of his process. Truax’s small intimate works were lined up on the wall, drawing us in to look closer at his “beautiful surfaces”. At first glance, the marks appear effortless like happy accidents and in a way, they are, though not without (a lot of) effort. The surfaces go through a process of building up and tearing down until they are finally considered to be finished works. The final pieces contain an ephemeral quality of what Truax calls “light” or “air.”

Stephen Truax is an artist living and working in Brooklyn. When he’s not painting, he’s curating shows or writing about art.

F: There’s a lot of history behind each of these canvases. There’s a lot of washing off, applying, building up and tearing down. How long does it take for you to make each painting? Can you describe the process for me?

ST: I have been working on the paintings in large groups, ten to twelve at a time, looking at them all at once, trying to make them work within the group, to build a network of relationships between the paintings. I don’t have a plan for what the paintings will look like in the end, but I try to not repeat the same color palette, composition, mark-making, or technique in any two paintings. It’s kind of the opposite of professional production.

Images courtesy of the artist. Photography by Jason Mandella.

Each painting presents its own set of problems and concerns. They’re linked by identical sizes and materials, high-key color, the level of finish, and the overarching concern of “light coming from within the painting,” which comes directly from Modernism. Working in series this way frees me up to treat each image as a proposition within the group. It forces me to challenge my conception of the kind of paintings I see myself making, or being able to make.

When a painting gets stagnant or starts to look overworked, I wash the gouache off in the sink, leaving only the pigment stain on the gesso or the painting is sanded down and repainted entirely. There is a build up of the paintings underneath the final pass that I think is so valuable in terms of “making light,” or “space,” or “air,” or talking about painting as a medium, or the history of each individual image.

My friend Matthew Miller makes fun of me for repainting them over and over, to avoid “ruining my perfect surfaces,” and my friend Nathan Dilworth loves to say in studio visits that my paintings are merely an excuse to hang a “beautiful surface” on the wall.

F: That’s interesting. How do your “beautiful surface” paintings relate with your photo work?

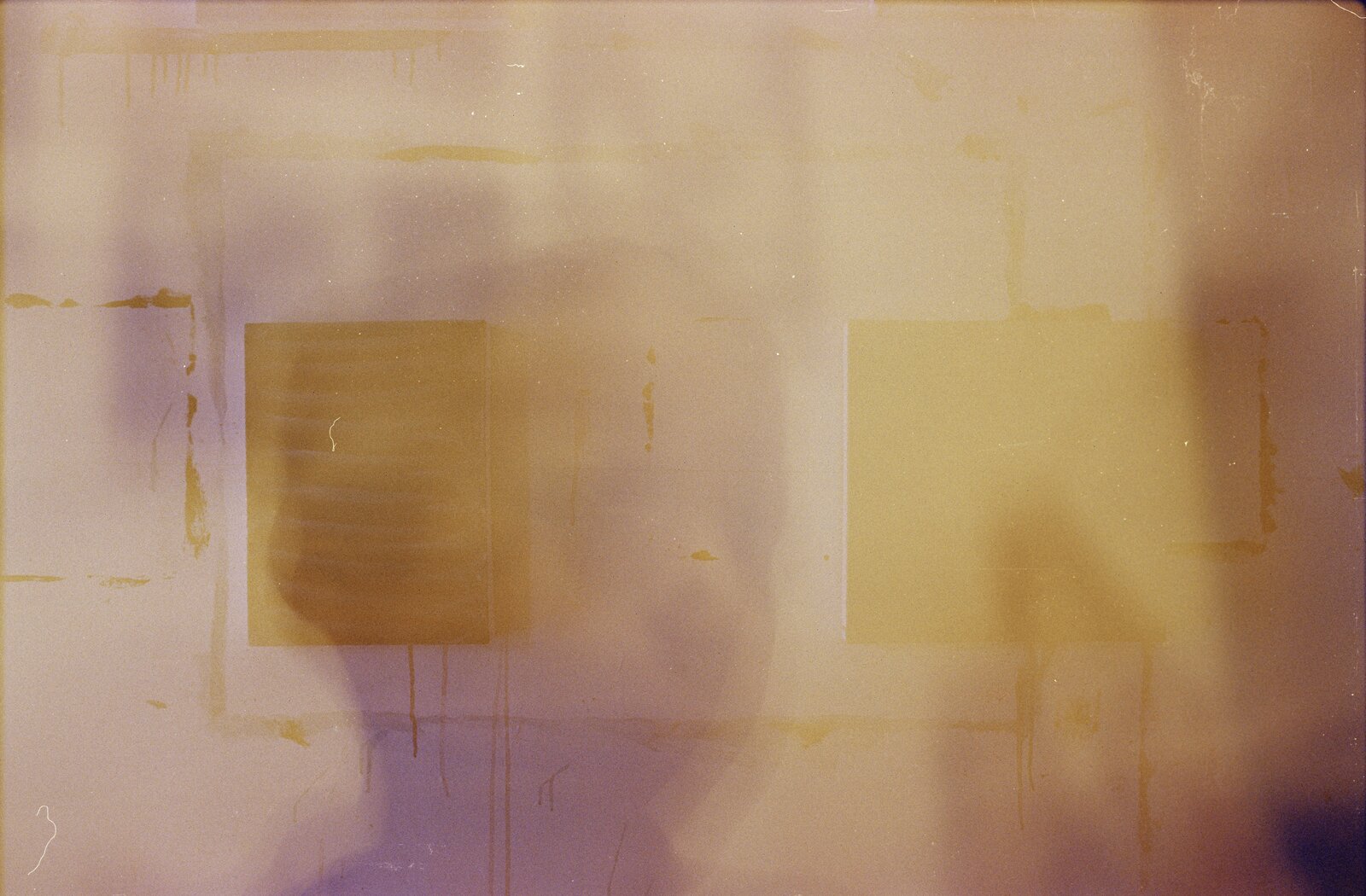

ST: This particular group of photographs, “Studio Shots,” were taken in 2008 in my apartment-studio in Bushwick, Brooklyn, so in that sense, they’re literally images of my paintings, or actions in the studio. But I only developed them in 2013, and started the project last fall. I am working with a professional photographer, and a friend of over ten years now, , who is currently an MFA candidate at Columbia College in Chicago, to color correct and print the images.

Because the images are double exposure film photographs, they are so over-exposed that there is extremely high saturation of color and information, which leaves the final image largely open to interpretation. Through a dialog with Scott, the color and transparency became the most important issues, and final result had a strong formal relationship with the paintings.

Images courtesy of the artist.

In addition to merely looking like one another, the two projects were made in tandem, and I hope that one will inform the interpretation of the other. I want the photographs to position the paintings in a critical, or at least a self-aware stance. Making paintings for me is a part of a larger project that is sort of me figuring out what it means to be making paintings right now, in the context of so many other artists (in Brooklyn) making abstract painting right now, and so much ongoing critical dialog and discourse that’s come out in the last few years on painting. Conversely, I hope the paintings color the photographs in a specific way that is about the concerns of a painter.

F: There seems to be a ‘wait time’ between each of the moves you make through the application or the removal. Is each move calculated or is it more of an intuitive gesture?

There is always a certain level intuition in every studio practice, particularly in the open-ended way that I am working. But the wait time you’re talking about – I call it ass scratching, which I take from Robert Irwin talking about painting – is I think the real work of the project. Rearranging the paintings into different groups, reworking the paintings that don’t fit, completely changing or painting over them is a very fast process. But getting all these elements to function as a whole is a challenge.

For me, these paintings ask a lot of questions about what constitutes a “finished painting,” and how a value judgement can eventually be assigned to a painting without many parameters about how it should look. I want these to stop when there’s just enough information to hold an image together without “completing” it. It has also been really interesting making all these different kinds of abstract paintings, and realizing that some were better than others, and trying to understand why. It makes for a lot of ass scratching.

Image courtesy of the artist. Photography by Jason Mandella.

F: There’s quite a bit of humor in each of these from the palette painting as a painting and the haphazard paint splatter on the photos after years of being in a studio. Where does this fit into your work?

ST: I love stand up comedy. I have been thinking about it pretty seriously for a while. I really feel that the job of the stand up comic is analogous to that of the artist. I love that metaphor. I really see Louis C.K. and Doug Stanhope as artists.

I use humor in my work as a way of visualizing or formalizing a healthy amount of skepticism about painting in 2014, and self-criticality, which is so closely related to the self-deprecating joke. I want the paintings to be able to be funny, as easily as they can be earnest, or sincere.

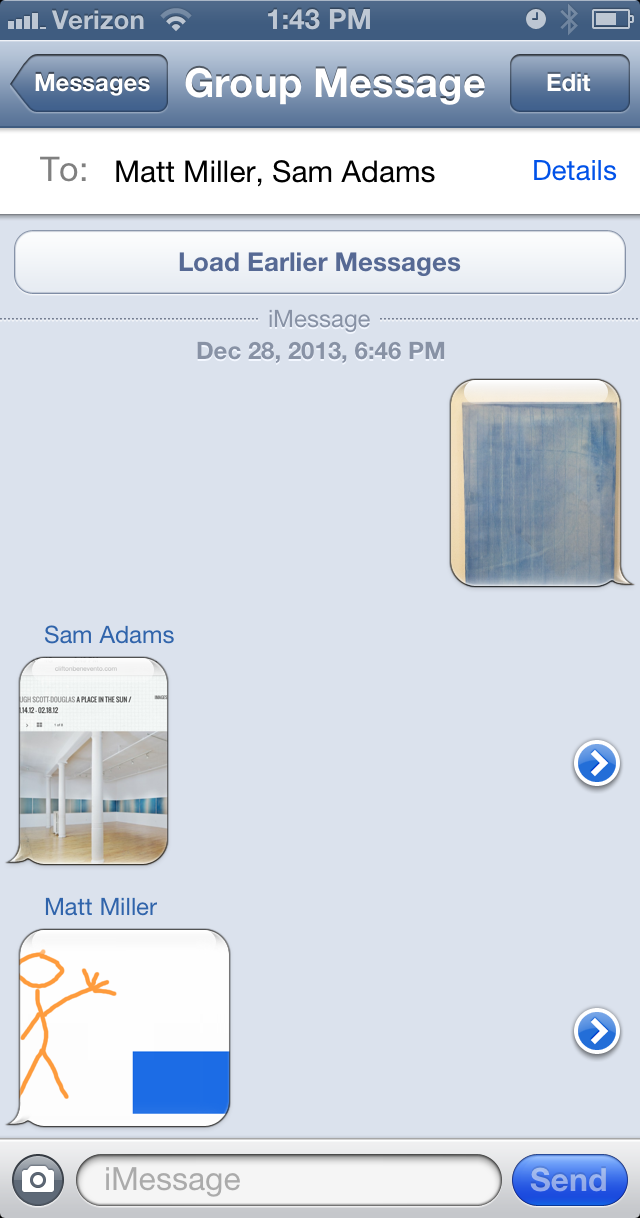

Of course, the funniness of my work is really understated, and actually might only be funny to me. Or maybe to me and my closest friends – like this text message exchange between me, Matthew Miller, and Sam Adams.

While this insider-humor might be lost on some audiences, I feel that the attitude with which they’re made could be picked up on by my mom, someone who has no formal training in art or theory.

F: Your scale is rather small and personal. There’s an intimacy with your work that only scale can achieve. Can you talk about why you chose the scale?

ST: There are practical concerns behind making small paintings. I want to be able to make global changes to a painting very quickly and see if it works – like experiments.

But additionally, they underscore handmade, individual production. I see it as an economic, if not political position. In a recent dialog, Lauren Portada said that she felt this was a “radical” departure from the commercial art world – mega artists, galleries, etc. – rather than the readily salable objects these small paintings appear to be. I really agree with that.

Images courtesy of the artist. Photography by Jason Mandella.

F:You mentioned that you use gouache. Do you use any other types of medium? How do you create those textures?

ST: All of the small paintings are made almost exclusively with gouache on primed canvas or linen. I am experimenting now with Guerra acrylic and Flashe. But the small ones are gouache, which is a high-pigment content matte designers’ paint, dries to the same color as it was wet, and is reworkable.

There is a dryness about them. The pigments sit on the surface. Some of the marks almost look like spray paint or airbrush. Is this a conscious “trick” or is it more about letting the medium react freely?

I use a lot of different techniques in all the different paintings: resists, pours, washes, wet-into-wet (bleeds), dry brush, scumbling, salt resists, and washing them off in the sink, Mr. Clean Magic Erasers, the list goes on. There is no build-up of paint because I paint thinly and erase so much.

The dryness you’re seeing is the gouache – the gum arabic binder – sinking into the gesso and canvas. I see this in direct opposition to the sexy, slick oil painted surface, which is so beautiful, but to me feels cosmetic, and possibly even gendered (male). I want my paintings to be “in” the canvases, not just on top of them.

You can see more of Stephen Truax’s works at .