‘s performance videos are entrancing though slightly difficult to watch as the viewer is made very aware of his or her own body. Cortney acts as Director in her latest pieces where she collaborates with friends and dancers to create these performances where the human body is put at a strain. The locations range from an empty dilapidated warehouse to a clear blue lake. We got the opportunity to visit with Cortney in her live work studio where we got a better understanding of how she puts these pieces together.

F: Can you talk about your process and how you start your projects?

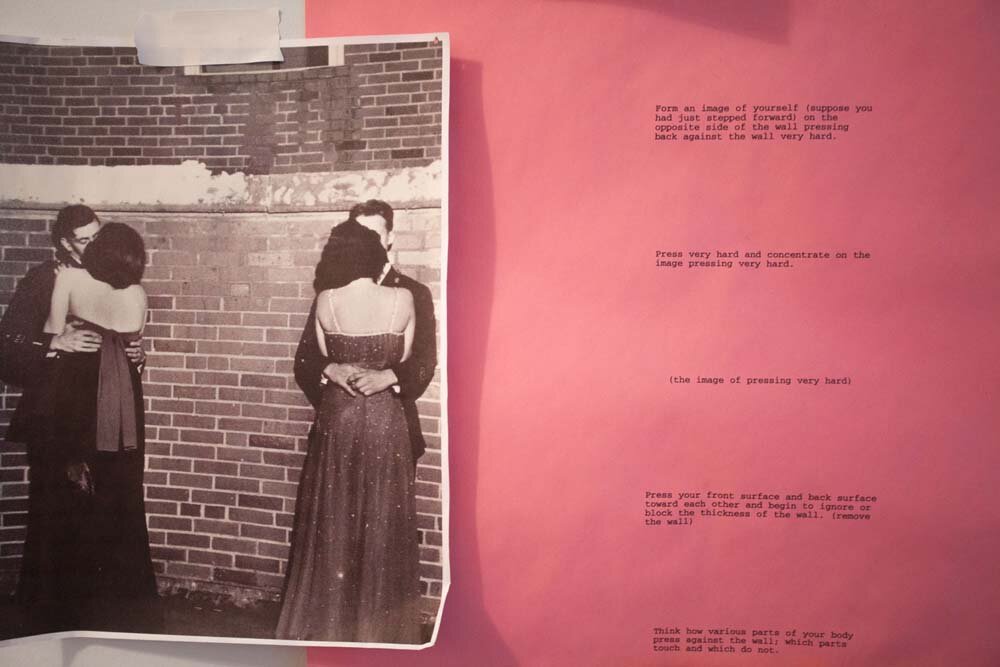

C: I’m interested in thresholds and boundaries, both psychologically and physically. I look for behaviors that express a duality, a subtext – when a gesture appears to be dominating, but is ultimately an expression of vulnerability; when a person appears under control, but you can sense an unraveling; sexual desire that hovers between violence and pleasure – the moment or space when a behavior changes from being exactly what you anticipate, to the complete opposite.

I find these dynamics in everything; I seek them out. I guess that’s the beginning of everything. I think I am most comfortable in those states— high intensity, uncertainty, with an implied boundary.

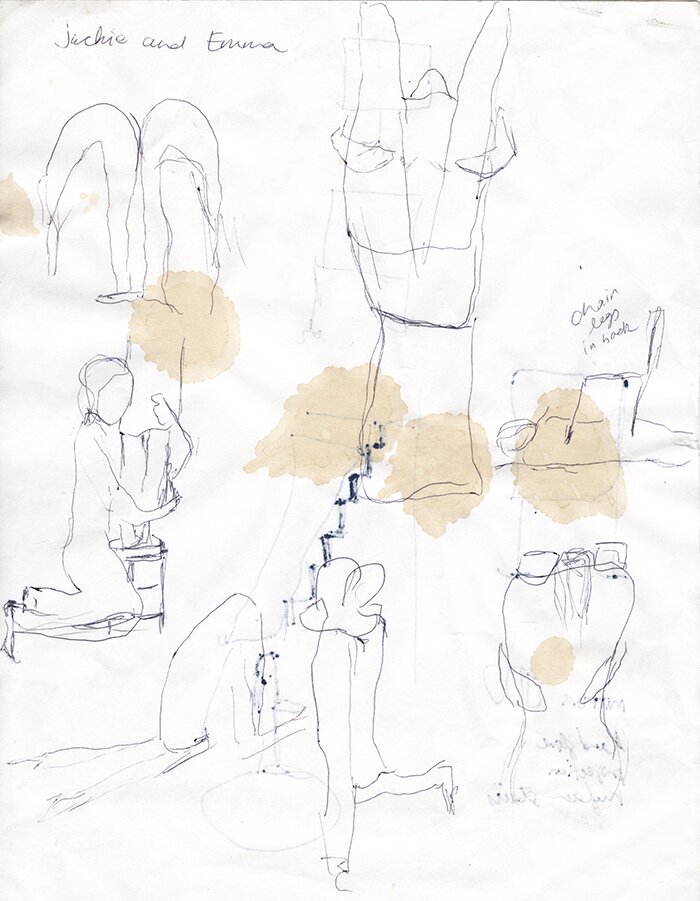

I write about these experiences, and try to understand their origins. I perform sketches, and make drawings and photographs before I start experimenting with more people in rehearsals.

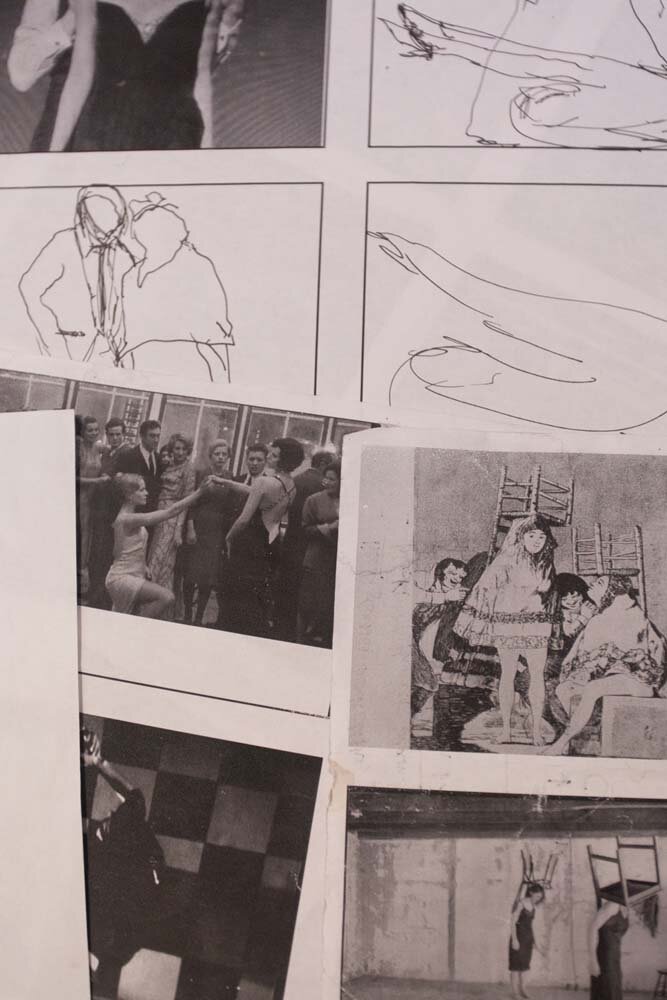

F: You start your projects with movie stills, drawings, sketches and photos that you have taken yourself. How do the films evolve throughout the project?

C: I talk about the scenes a lot. It’s all very psychological and I intuitively understand it sometimes to the degree that I no longer see it. The way people don’t see themselves. Talking about it and performing it, even having someone repeat it back to me in their own language helps me to understand it. Those conversations shape the piece in progress, and that is really what rehearsals are—a visual conversation.

F: Is it as much a collaborative project with the performers and people that you work with? Can you talk more about that?

C: It has to be collaborative when you are working with so many people. The performers bring themselves to the work, and that is important. I choose and direct them to a certain point, but I don’t want to control every detail. I’m interested in communicating the idea and I like to remain open to the different interpretations of that idea when I watch people in rehearsals. It would be boring if everyone translated a task or a feeling in the same way.

I learn more precisely what I want by watching it unfold, which is the nature of my work.

When I work with a crew, they are as much a part of the collaborative process as the performers. It’s a small crew and everyone has multiple roles to fulfill.

I work with people that understand the power dynamics at play in my work. I like being able to work with all of these really talented people, who bring something different to the table.

F: It seems like a very demanding process and very taxing to the performers. How does this play into your work?

C: Are you relating the challenging physicality involved for the performers to the challenges involved in producing the work? I’ve realized that I am actually performing the same thresholds as a director that I am asking of the performers in the work.

Because I’m not performing in the work as much these days, I think I recreate that physical challenge by pushing myself as a director. It’s become about the process of making these videos and testing myself- how far I can push myself physically, mentally, emotionally and financially.

Of course, there’s the belief that asking people to perform physically exhausting tasks is sort of sadistic, but I think a lot of people like that challenge – it’s gratifying.

F: Some of your earlier videos include you as one the performers. How did this change the overall piece and why have you decided to not include yourself?

C: Since grad school I’ve been in most of the work, but not usually in obvious ways. I tend to hide, but I wouldn’t say that I’ve decided not to include myself. I am still performing in the recent works. I’ve become a director because I’m working with more people.

I still come up with the gestures, positions, and choreography by practicing and then photographing it. I like figuring things out that way, because I intuitively know something is good when I am physically doing it. Unfortunately for the performers, I usually know it’s good when it hurts.

F: The performers backgrounds are mainly in dance. How does this change the way you communicate your ideas or convey what your concept is? Does this change the overall feel of the film?

C: I approach the films as a visual artist and generally everything I ask the dancers to do is something I have done. I think we bring different things to the work because of that.

Everyone uses their body to communicate, it’s universal. As a woman and an artist performing in images, I’ve always been very attuned to that language.

My ideas are based around communicating emotions through the body, and that is a very human thing. Dancers and actors are trained so they are more aware of the nuances of this communication.

The main difference is that dancers and performers are more familiar with the physical discomfort that comes along with this kind of work so their threshold is often higher. They know their bodies. If something is wrong for their body, they figure out a way to do it so it works.

It’s important working with people that are able to let go. You really have to be able leave parts of yourself out in order to be present. Or maybe I mean hold back–holding back parts of your self. That’s when it gets powerful because you begin to see the threshold of the body, and the person, beneath the surface of the performance. It’s more honest.

F: The video you are currently working on was shot in Skowhegan using artists and instructors. Was this different from your other projects working with professional performers?

C: I’ve only been working with dancers/performers since 2012. In my other work, I’m usually performing along with my friends and lovers. The majority of my work has been created with people in my life who are not performers.

F: How long does each performance take from early development to completion? Do you work on multiples at the same time? Does the time between filming and edit change how you look at the project?

C: It takes a while. I’m working on several things at once, until it comes time to do a big shoot and that completely takes over everything.

I can’t dig into editing the footage right after a video shoot. I need some time away from it. There’s such an adrenaline rush while doing it–all the production, the rehearsals, the meetings, the scripting, the photos, the equipment sourcing and scheduling. It all comes together for 6-8 hours, and then it’s over. It’s sad when it ends.

F: How do you find the places to film? What are the logistics of finding the space, renting the space out and finding costumes?

C: I’m scouting locations constantly. It takes a lot of searching to find a place that will host a shoot with a very small budget. And then it’s all about the schedule – getting 15 people together at the same time the space is available is actually the hardest part. Costumes are usually from my closet.

The props are sourced from all over. I just bought 100 wine glasses for a video I shot, and now I have milk crates full of glasses in my apartment. I don’t know what to do with them.

F: Do you see your photographs as a separate body of work than the videos? Do they inform each other?

C: The processes are really different for each. The photos generally come first and inspire the videos—not always, but that is the current process. It’s that thing again where I have to see it to know what to do next. I’m a photographer at heart I guess.

You can see more of Cortney Andrews’ work at