is an artist currently working in Montauk, New York. He graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) with a BFA in Painting in 2011. He has had solo shows at (New York), (Houston) and has recently been part of the at the PIMA Air & Space Museum (Tucson, AZ)

F: The objects, how sturdy they are and how heavy they are, completely changes the way that I look at these things. I look at them as a solid mass.

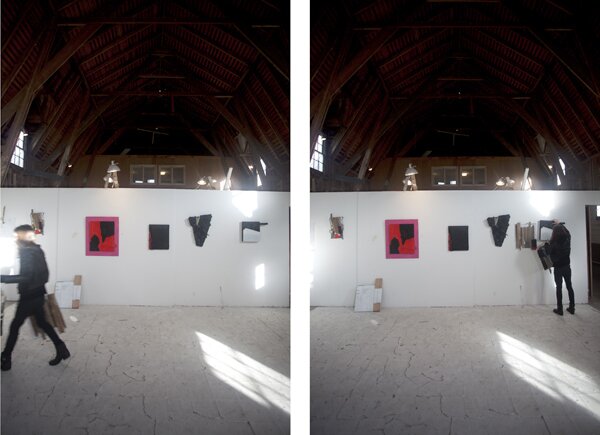

AM: I’ve been more conscious of trying to make them be sturdier. The first show I did, I felt like everything was very frail. I was sewing into the pieces a lot, using hot glue. Now I’m using gorilla glue and I’ve been nailing everything down. These are very much sculptural. That’s part of the process. I just start tearing and nailing and using things not really knowing where I’m going.

F: So it’s more about the dictation of the found materials?

AM: Yes, in a way. It’s a tough balance. I often choose materials I think look great on their own, like these scraps of denim, but the work is all about manipulating them.

F: Then that becomes another dialogue in itself or vocabulary that you couldn’t even expect from before.

AM: You can’t be too precious about your materials. I find that to make them work in a piece, I have to alter them. Maybe I’ll soak them in paint, or tear them up. Then they start to take on new characteristics. Different weaves of fabric take the same paint differently, and that is important. And when I do use an old garment I’ve collected from somewhere, and I tear it up, I end up with seams and shapes I would have never arrived at on my own. Those seams and half-random shapes play a large role in my compositions.

F: Not only are you using that idea but also pointing that out by the red paint mark.

AM: Right. Because that line has become part of the composition of the painting. For whatever reason I decided it should be emphasized.

F: Do you ever take those out afterwards?

AM: Sometimes. Or I soften them. I can draw attention to them or subdue them. It just comes about from me looking at the painting a lot. The pieces are very three-dimensional, but those decisions have to do with the two-dimensional composition, which is still a major focus. I say the painting is finished when it seems to appeal to an intuitive sense of order that I have.

F: Then it becomes about building it up until you can find that order.

AM: Right. As I work, I feel like I’m sort of wrestling with the decisions I’ve made earlier in the painting. I’m constantly re-assessing what I have already done. Because I can slap any number of things on the piece and have it look interesting, but the goal is to get to a point where I can look at it, and say ‘Okay this makes sense.’

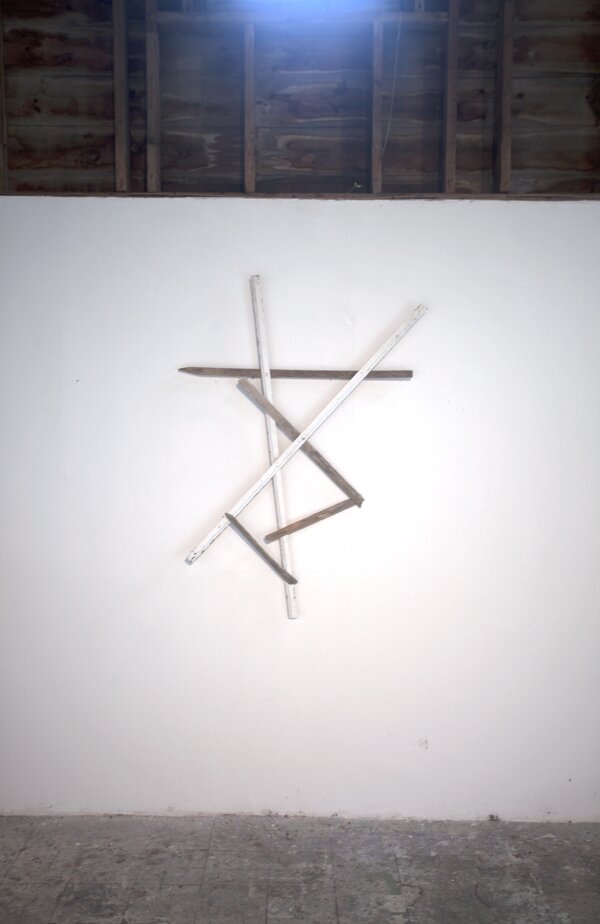

F: This large one that you did. It seems like there’s a very specific order in a very specific way versus the one that was hanging up here. You’re doing the same things with the jeans and the t-shirts, that you’re now doing with the cardboard. It seems more logical or more considered in some ways.

AM: A lot of the lines in this piece were found, not invented. What’s creating the lines is where the sections of cardboard meet. I think that having this big plank of wood nailed on top is sort of a similar idea where I take the material and I lay it there and let it be.

F: Its so easy to translate this [the materials] from a large brush mark in a way.

AM: It does look like that. It’s something I thought about when I saw that [knotted wood that juts off of painting]. The texture of that plank of wood looks like a thick brushstroke. That’s sort of how I was thinking of it. I don’t know if I ever answered your question about breaking the rectangle, but that’s what I think of it as – a big mark where I take something and put it on there, breaking the boundaries I had set for myself by choosing the rectangle in the first place. It shows that the real work isn’t about about this square. It’s about what I’m doing to it. It’s not about the rectangle itself. Again, it’s an additive, sculptural process.

You can see more of Alex Markwith’s work at