Inside ‘s studio, there are multiple pieces in progress and it seems as though he has his hand in almost every type of medium including music, film and painting. Cooper’s paintings rest on the line between the digital and physical constructions. From first glance, the domestic imagery looks pretty straightforward but after a second much closer look, the subtlety in the layers of paint applications and transfer processes indicate a much more labored process. With each added process or step, each painting becomes more in depth with more detail emerging. After talking with Cooper, we discover just how much planning and thought is involved and the exactness of each step. There is a linear methodology to his process which reflects his MFA printmaking background at RISD.

Unstructured with works by Cooper Holoweski is currently on view until September 1 at

F: Can you talk about your process and the medium you use? There is a push and pull from the paint and the transfer process and it’s hard to tell which steps come first and which come after.

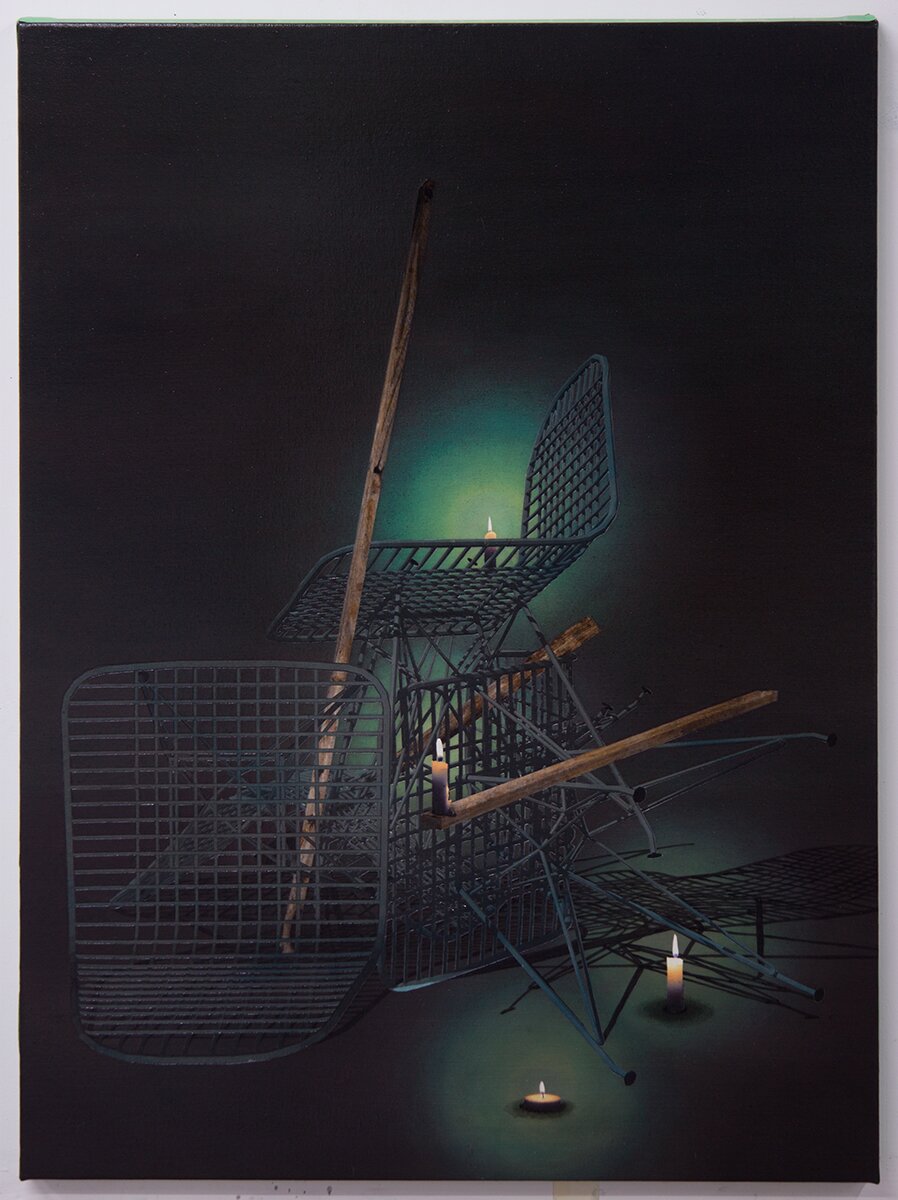

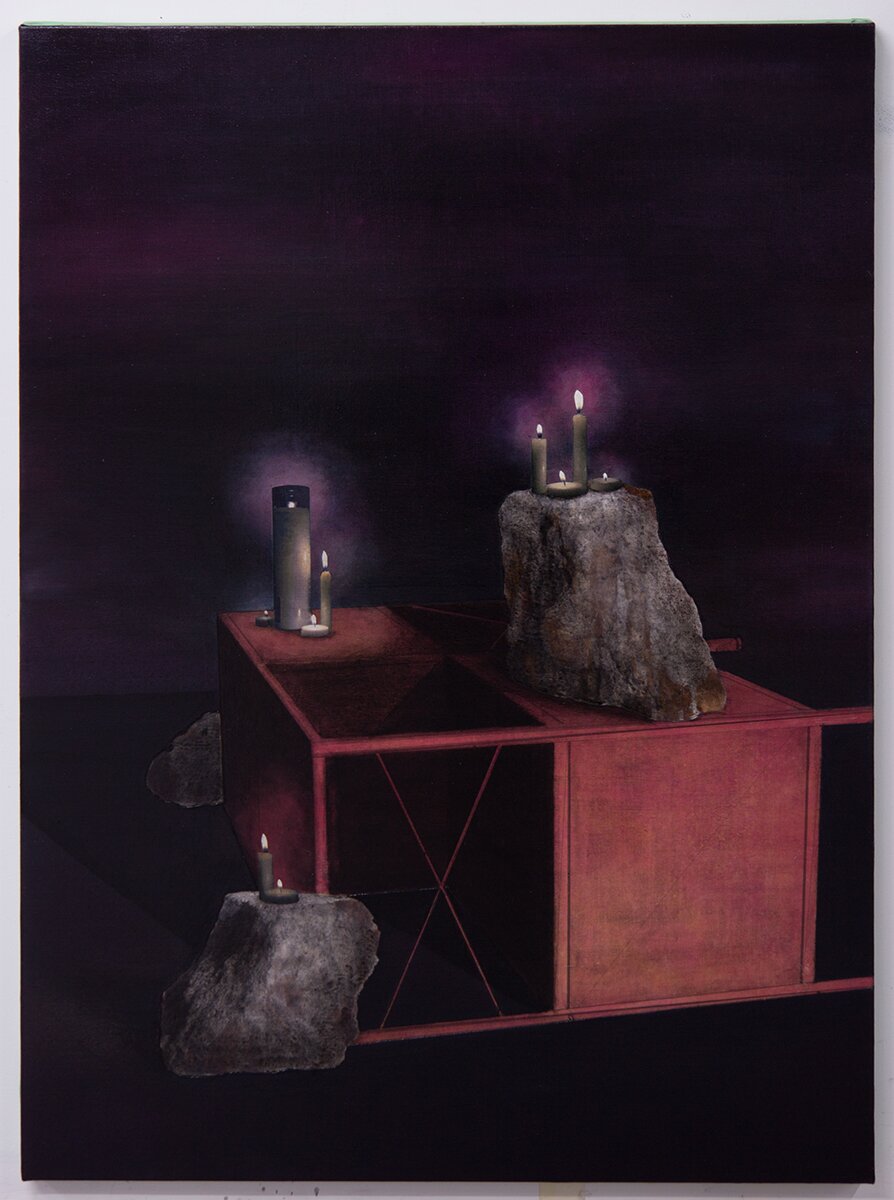

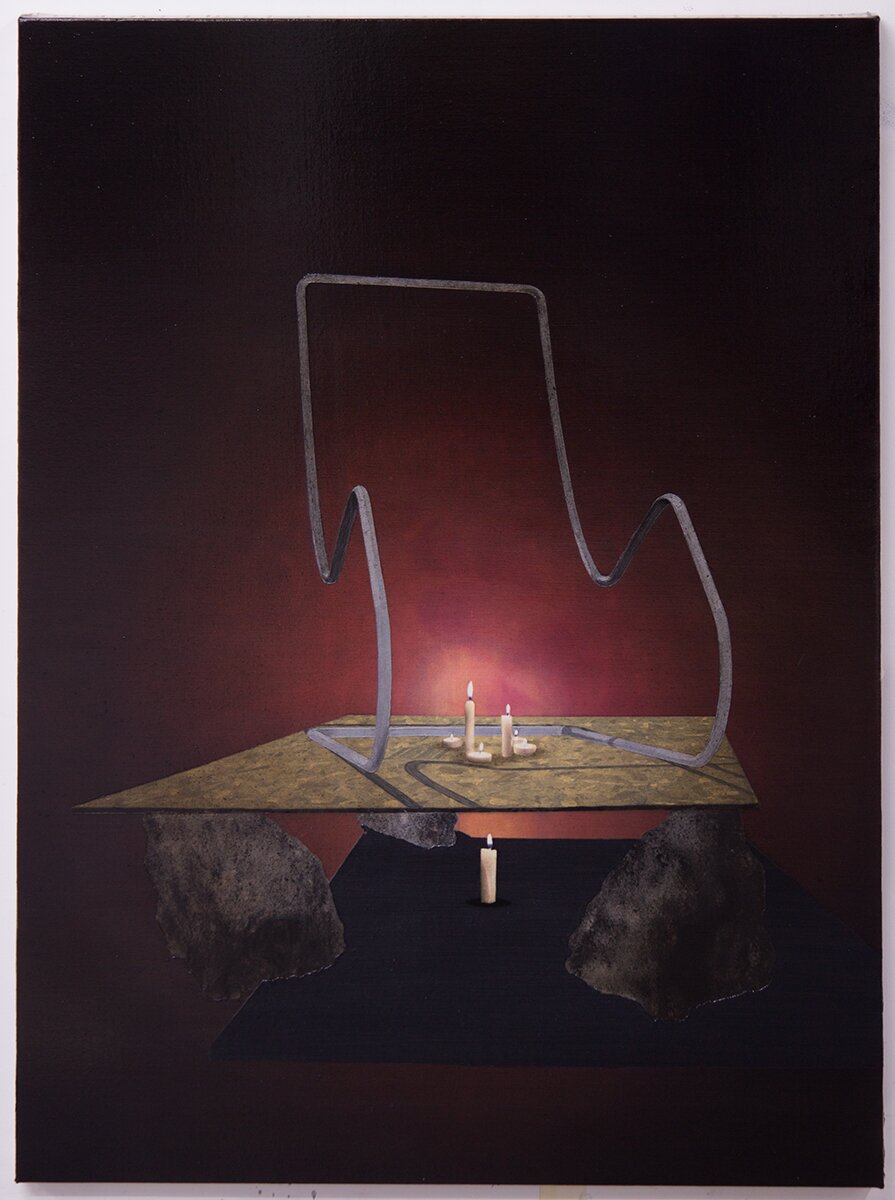

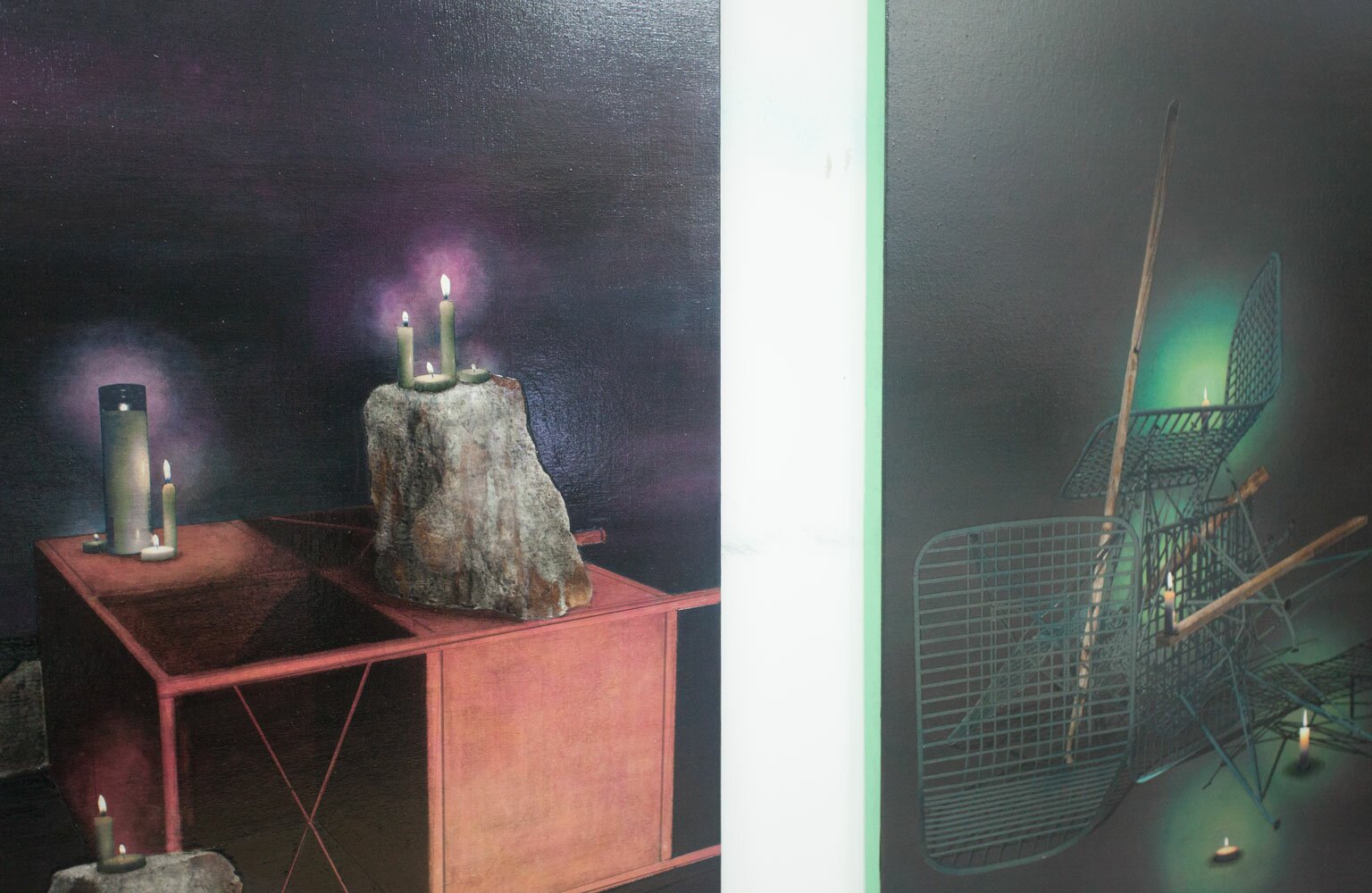

CH: There are a couple of different things going on and each piece is different but for most of them I started by staining the canvas and transferring the still-life via acrylic gel, then lots of masking, painting, and blending to make things cohesive. I add a lot of really thin coats of paint that I wipe away in areas that I want to glow. I really want them to look unified from a distance but break apart the closer you get. They have this old-masters vibe about them at first then you start to realize that all the pieces of furniture are digital 3D models and the rocks are photo transfers and candles are inkjet prints and they reveal themselves as a weird stack of collaged materials.

F: How are your images conceived?

CH: They all come from a pretty intuitive place. I mean, the imagery is undeniably loaded but the overall compositions are all from sketchbook drawings that start off really playful. The first one I made was the one with the Noguchi table on top of the cinder blocks and I just had that image in my brain for a while and I wasn’t sure what it meant our how it should exist in the world. It was like that scene in Close Encounters of the Third Kind where Richard Dreyfuss is making the plateau out of the mashed potatoes. At one point it just struck me that the furniture elements should come from digital 3D models. They are such idealized objects and it felt really appropriate to pull them from that realm where everything exists as a perfect version of itself. So there is this push and pull between logic and intuition in how I build these things and that seems to carry into their final state.

F: How do the video pieces and digital prints work with the paintings? Do you see them as separate and equal or more of one influencing the other?

CH: All of the work has a similar process of combining digital 3D models with photography and something more tactile (paint, clay, ink, etc.). The prints are really different thematically though; they come from very specific places and are loaded with personal narrative. The print series is called “Memory Palace” and each one is a mental reconstruction of a place that I’ve lived or spent formative time. So one of them is a scene of my dad’s apartment in 1989 and it has all these elements from that space that I remember. I’m sure I’ve missed some things and added others to these spaces and that’s the point.They’re very flawed reconstructions that are cobbled together from Cinema 4D and SketchUp and digital photos and scans of ink washes and google images and a bunch of other sources, and it all adds up to this vivid and surreal image.

My video piece Katabasis and the paintings come from a similar place to each other though. They’re imbued with personal narrative too but it’s a lot less specific. To me, the video and paintings are responses to “what happens after the collapse?” They both situate you in that aftermath. The cause of the collapse is not really important but the tour of the wreckage is, and so are the weird beliefs that people hold onto and the objects they find sacred.

F: With the video work, there is a performance element alongside it. Can you talk a bit about that?

CH: The video (Katabasis) comes in two forms, and it sounds silly but I think they are distinctly different even though they are visually the same piece. So there is a version of the piece with a recorded soundtrack. It’s a self-contained video that can be screened anywhere and as a viewer you can walk in and out of it, and considering that it’s 40 minutes of a single tracking shot you probably will.

CH: The other form of the piece is to have it screened with a live band performing the soundtrack. For me, the live instrumentation makes it less about the formal aspects of the video and more of an emotionally cathartic experience. The drums are loud and the three of us give it our all every time we play. We also tend to change things up musically for each performance it so there is this ephemerality that contributes to that feeling too.

CH: There are 3 movements to the piece and if you see it performed with the live soundtrack, I think you’re more likely to experience the piece from beginning to end. That’s just the nature of things, people are more likely to loose themselves in the experience of a performance than a looped video. That being said there is a certain intimacy in the experience of watching the piece with the pre-recorded soundtrack. The piece itself is based on the cyclical narrative of death and rebirth so I also happen to really like the idea of it being looped and people only catching parts of it at a time.

You can see more of Cooper Holoweski’s works at www.thisisprogress.net.